Is The NYT Jones Day Take-Down Actually A Take-Down?

What's most interesting about these two NYT Jones Day stories is just how different the upshot of each is.

It’s not often that you open up the New York Times and see a major investigative story on a Biglaw firm. But in late August, the NYT Magazine ran a sprawling story on how Jones Day purportedly reshaped the American judiciary by masterminding and orchestrating the appointment of a massive number of conservative judges, including no less than three Supreme Court justices.

A few days later, it ran another extensive piece on how Jones Day successfully defended and settled cases on behalf of Abbott Laboratories in a string of cases related to allegedly contaminated powdered baby formula through “scorched earth tactics.”

These articles are unusual. Set aside the fact that often these stories aren’t told because a generalist audience might not find them interesting. Many publications shy away from directly reporting on top law firms for fear of becoming embroiled in a dispute with them — a sort of implicit recognition that the firms are so powerful one might not want to cross them.

For instance, when I’ve written pieces about law firm practices for some publications, I’ve been asked to remove the direct naming of the firms and instead replace that with general descriptions (so imagine instead of me writing this piece directly saying the words “Jones Day,” I’d be asked to refer only to “one of the largest international firms.”) Above the Law has never asked for such treatment and provides a platform for honest discussion in pursuit of improving the industry. Yet, there aren’t many similar avenues. The fact that the New York Times is going full throttle is unique.

These two stories are adapted from “Servants of the Damned: Giant Law Firms, Donald Trump, and the Corruption of Justice,” the tell-all book by New York Times reporter David Enrich which comes out Tuesday. In it, Enrich apparently also reports that Donald Trump tried to pay a white-shoe law firm with the deed to a $5 million horse rather than pay an outstanding $2 million bill.

What I think is most interesting about these two Jones Day stories is just how different the upshot of each is, yet both are written in the spirit of revealing that the law firm is something approaching out-of-control.

In the case of Enrich’s reporting on the evolution of Jones Day into a conservative political force, the reader is confronted with the need to assess whether this is a good or fair thing. The implication of the article is that it is not.

Should a law firm become so enmeshed with a presidential administration that it is hard to “distinguish where Jones Day’s interests ended and the Trump administration’s began”? And if that is fair play in a world of corporate influence and revolving doors in Washington, is the net effect of Jones Day’s influence — which Enrich reports to be to have “helped erase the constitutional right to abortion, erode the separation of church and state, undermine states’ power to control guns and constrain the authority of federal regulators” — good or bad?

In the case of Jones Day’s work to defend Abbott Laboratories, the upshot is that actors like this law firm can help corporations avoid liability for product safety claims through aggressive tactics. The implication is that there is something wrong with this.

These of course are two very different judgments to draw.

As anyone who has followed my writing knows, I believe that there is an increasing imperative for corporate legal departments to be aware of the values of their law firms. Boards are demanding supply chain accountability across issues like sustainability and diversity. 97% of general counsels say they would take action if their law firms didn’t match their values. So, this reporting on one of the most prominent international law firms is a major contribution of data that in-house teams can draw upon when deciding who to work with.

But what is easy to miss is that there are no universal values. The subtitle of Enrich’s book about the “corruption of justice” is a categorically opinionated view (as one should be when writing a book). Of course, what that means is that those on the other side of the opinion would probably disregard it as having an agenda and, thus, having no signal. Instead, we should catalogue the facts for future reference.

If you work in a corporation whose public policy efforts align with the direction Jones Day has been pushing America, this would be evidence that they are a great fit and a cause to support. There may be cases where an enterprise absolutely wants a law firm to use “scorched earth tactics” to win. Of course, if the company you work for is pro-choice and anti-guns, or perhaps supporting a broader progressive agenda, then you might think twice about whether they are the right firm to work with in general or on particular matters.

The upshot of all of this is to realize that pretty much everything written about law firms is biased or opinionated. It’s either propaganda (also known as marketing) about how they are the best for their clients and the world or it is reporting which attempts to expose how they aren’t through truth-telling. Somewhere in the middle of all of that are facts being revealed and uncovered about what the firms are actually capable of and what their values are.

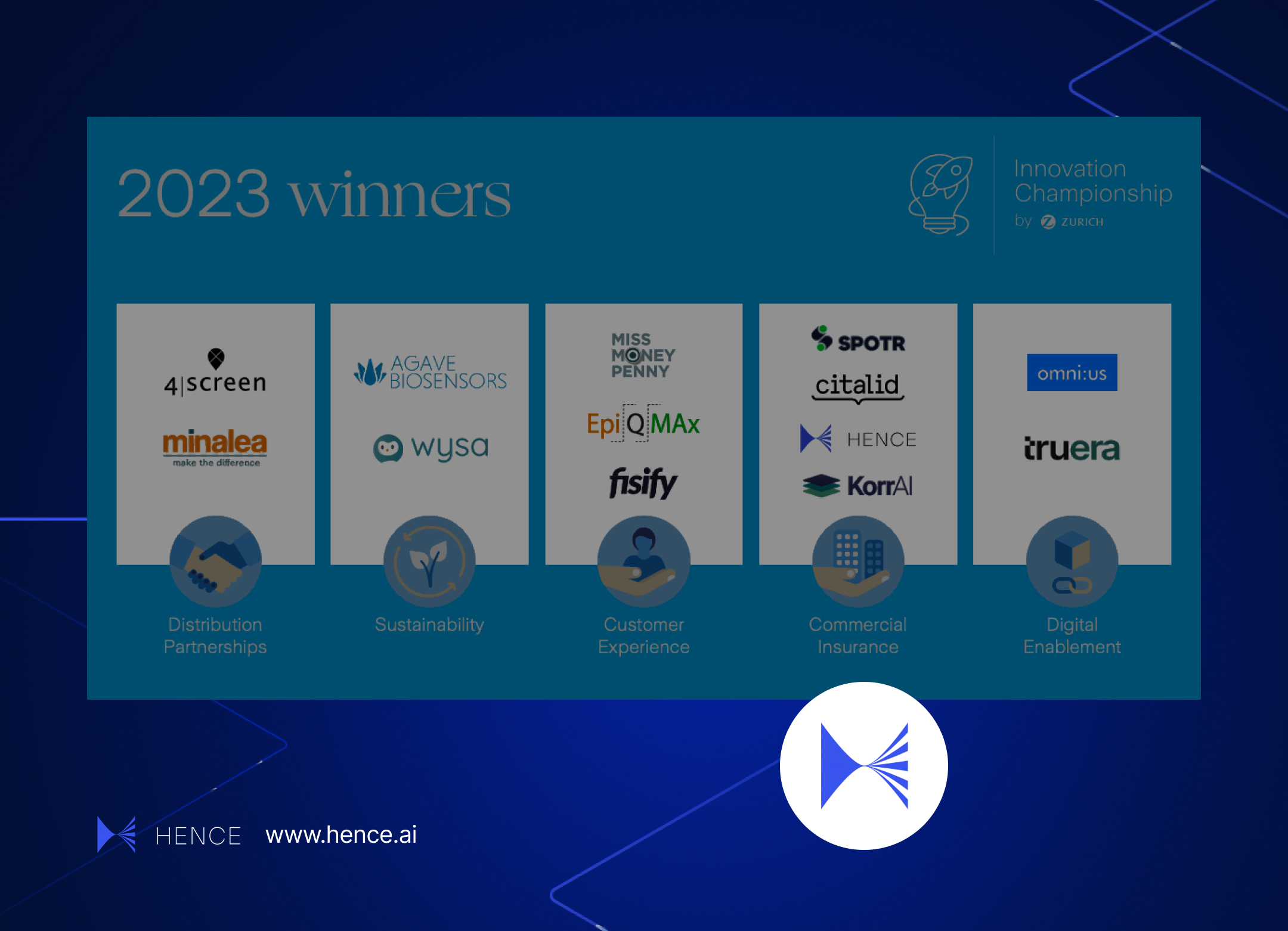

At Hence, we’re working to bring this type of data to the moment of selecting a law firm. If an in-house counsel who knew little of Jones Day’s reputation was tasked with vetting the firm, they would probably turn to Google Search, which would turn up both these news stories — and perhaps that of a recent data breach. This search would present information completely out of context of the firm’s broader history or relationship with the corporation. By systematizing the collection of such dots of information, we can create a basis for corporate leaders to choose who is a good partner and who is not. While I am arguing against there being an objective good or bad judgment of these firms, I am arguing that judging whether your law firm partners best represent you should include an assessment of the other actions they take. While one can argue that everyone has a right to their own defense, the line between politics and law is very fine, particularly when it comes to outcomes which set legal precedents that override political choices.

We should applaud anyone willing to document in painstaking detail the actions of law firms, as Enrich has, where that would otherwise be left unsaid. But we should be thoughtful in drawing our own conclusions about what’s being said from our own perspectives.

“By SEAN WEST, originally carried on Above The Law”