The 4 Reasons Every Law Firm Wants To Do Geopolitics — And How To Know Who To Trust

The political context of everything matters.

Why are law firms increasingly getting involved in geopolitics?

As Joe Andrew, the founding global chairman of Dentons quipped in our recent sit down: “A good lawyer knows the law but a great lawyer knows the judge.”

One could interpret that adage as implying a personal relationship between the attorney and the judge that is somehow more deterministic than superb legal work. But to me it simply reflects the fact that context matters: If you don’t understand what you’re up against, you’re unlikely to be successful.

And in today’s world, the political context of everything matters.

I served as Global Deputy CEO of one of the top geopolitical advisory firms, and my experience historically was of political and legal advice being quite separate. The CEO or head of government affairs needed to stay abreast of all political changes but the legal department only deeply engaged if something very acute was happening with a clear political angle. So specialist advice was bought in from top flight forecasters like ourselves, none of whom traditionally sat within integrated legal offerings.

Law firms historically provided public policy and lobbying services. But when it came to “geostrategic” work — or forecasting of global events — they typically stuck to “loss leader” political content to prompt conversations. For instance, every law firm in the UK held seminar after seminar to launch paper after paper about BREXIT, but few were courageously forecasting outcomes. Most were producing unenergetic summaries of regulatory changes that were possible (not probable or improbable). Useful enough to hear once over a mediocre croissant, but not more.

This is all changing. A number of firms are placing big bets in the space. Dentons, the biggest law firm in the world by number of lawyers and number of active geographies acquired top-flight global political strategy firm Albright-Stonebridge and EU-focused public affairs firm Interel last year as anchors for its new Dentons Global Advisors business.

On the other end of the size spectrum, Avonhurst, a London-based “new-fashioned law firm” where I’ve served as senior advisor, launched three years ago as an integrated legal, legislative, political risk advisory, and capital services firm with a roster of former top White House and British political and military advisors sitting alongside White and Case’s former head of London Litigation and Womble Bond Dickinson’s former head of white collar crime and investigations.

Others, like Arnold and Porter, have stocked up on nonlawyer diplomats like Ambassador Tom Shannon, who has served as acting U.S. secretary of state, for international troubleshooting. A host of other large firms are beefing up their public policy teams with nonlawyers who provide strategic advice, not just lobbying work.

Here are the four reasons this is happening now — and what in-house leaders need to know to make the most of it.

1. Complexity. Read the newspaper, and it’s obvious that political cross-currents are less predictable, and the speed of political shifts is increasing. Fortune 500 companies are increasingly doing deals that span dozens of countries, and local knowledge about the political context in which such deals are getting done is increasingly valuable. Or, conversely, pursuing complex cross-jurisdictional matters without knowledge of the geopolitical landscape increases the chance of failure. “Every deal that’s more than $1bn crosses over a minimum of 12 countries — transactions are significantly more global every year… clients come to us because there’s a dispute in 104 locations and 70 countries” said Dentons’ Andrew, whose firm claims coverage of 209 locations.

At the same time, there is massive investment in emerging technologies where the law is being written at the same time that it is being practiced. Foresight — and the ability to shape outcomes — in that type of world matters. A lot.

2. Role of the general counsel. Rather than a world where politics is handled by the CEO and government affairs, more general counsels are finding themselves central to board-level decisions that have a political angle. Some of this has to do with the complexity outlined above crossing over into strategic responsibilities that fall under the GC’s purview. Some of this has to do with the evolution of the role of the GC, as Ben Heineman articulated in Inside Counsel Revolution. And some of it has to do with a sense that doing political work under privilege where possible is a good strategy. But the pandemic has also been a big accelerant too, as GCs found themselves sitting squarely in the center of so many ongoing business decisions. As a result, GCs need their own advisors in order to help guide the business.

The benefit of an integrated political and legal approach is that the teams are working together in lock-step, so theoretically can respond faster and with more precision to help the GC advise the board.

3. Evolving business models. Law firms are always looking for ways to expand their business and the unique role that lawyers play — with access to huge amounts of information and interconnected networks — is a unique opportunity to monetize what they know about political activity.

Being able to mobilize a team of in-house public affairs professionals as part of a coordinated strategy for winning a client’s issue or a case no doubt provides the law firm fielding that team the ability to add a host of new hourly fee earners to the bill. When those fee earners cost less than lawyers of equivalent stature, that can translate into mega-profits for the firm. So this seems attractive on the face of it.

But this can also be a problem if the law firm and customer incentives aren’t aligned. As Matthew Oresman, head of international public policy and partner at Pillsbury, Winthrop, Shaw, Pittman tells me — “We need to be selective about the problems we’re solving. If you bring me a political question and I’m just going to have to put a bunch of first years on it and charge you a large amount to give you a report that’s fully desk research and not based on real political experience like you’d get at Eurasia Group or Rice Hadley Gates, that’s not good value for the customer.” Jonathan Bloom, chairman and CEO of Avonhurst, solves this problem by having eliminated the billable hour across the board at his firm. “In Biglaw you have lots of lawyers billing hours and not necessarily aligning interests with their clients. We are building teams aligned with the clients and getting paid as and when our clients are realizing value — not just because we spent time with them. That’s the only way to truly integrate political and legal work.”

4. Integrated outcomes. One-stop shopping is always more convenient, but only if you can get everything you need without compromising quality. Oresman is enlightening on this point:

Done right lawyer-lobbyists and lawyers giving geostrategic advice can do really well because they see so much industry, geography, transactional, and risk management work. So much of policy making and risk management has a legal or analytical angle, so lawyers have inherent skills to understand the problem and develop solutions. The trick is finding lawyers who offer holistic solutions — things that aren’t just law suits or regulatory petition but communications, lobbying, legal, grassroots — all the different elements of a solution. Think about driverless cars — you can hire a law firm to help you understand the regulation but what you really want is a lawyer that will sell you a comparative regulatory study to tell you where to do your project, help get the law changed to shift the regulatory environment by lobbying the lawmakers and regulators, and use grassroots to get a better environment for what you’re trying to achieve.

Now if that integrated strategy exists, it sounds a lot more likely to be effective — and more user-friendly — than cobbling together a host of independent providers.

So, this type of innovation in and around the legal space surely creates more options for general counsels and in-house teams to get legal advice integrated with political advice. And no doubt, such legal advice is better as a result. But there are a few trap doors to be aware of.

First, every firm has a bias — whether geographic, political, or through some other type of perspective. So while it’s tempting to rely on one set of political advice, it may be harder to nail down the actual source of that advice when it is coming from a big law firm alongside legal advice. It’s worth the effort to do so.

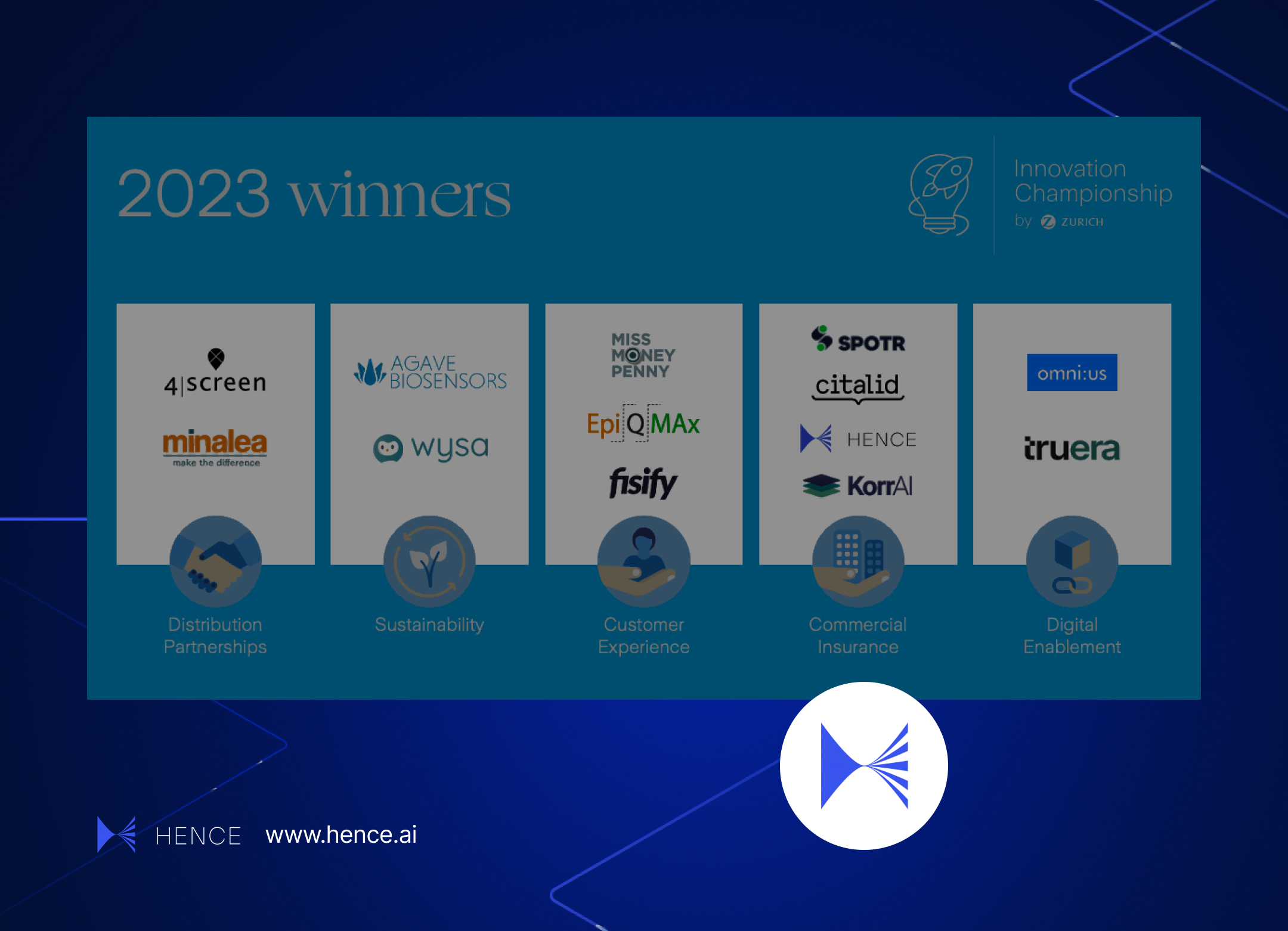

At Hence Technologies, which I co-founded, our software helps companies select better lawyers and de-risks legal selection. So we spend a lot of time asking questions like: Who are the beneficial owners of a particular law firm? Did they generally come from one school of thinking — politically or even literally did they all go to the same school? When I’m receiving a piece of work from a large firm, do I know who actually performed the work and was it done in-house or was it outsourced to someone else with their own biases? When I uncover biases or work that falls short, can I keep track of that so I don’t make the same mistake again. This is absolutely critical with respect to integrated legal and political advice — particularly when the lawyers buying the work are not political experts themselves.

Second, realize that to get a political problem solved, you probably still have to pay for multiple advisors. Often there can be a sense that political advice is somehow less specialized than legal advice — that relying on the opinion of one expert or one firm is all you need. To be clear, the firms with the largest breadth of political coverage very well might be the only call you need to make to get to a quick temperature reading on a multijurisdictional issue. But if you’re really hunkering down into trying to shape your environment or win a major case, it’s important to have all bases covered. Thinking just about Russia-Ukraine, one might need political advice from an American, Western European, Eastern European, financial regulation/sanctions, and then sector-specific perspective just to get started to really understand the picture. Oh — and those are just the political advisors.

Third, recognize that the advantages lawyers have by “being in the mix” on policy-making can also be a constraint. If a lawyer learns something is politically likely to happen because of work they are currently doing, that would seem like an advantage. But not if they can’t tell you because it would create a conflict with their initial client. So advice can end up being diluted and less specific to manage these conflicts.

On the whole, the market is better off to be able to buy legal and political combo meals alongside the traditional need to order separately. However, it’s important not to lose sight that the whole reason this is possible is because politics is increasingly complex.

“By SEAN WEST, originally carried on Above The Law”